Changes are afoot for Cincinnati residents — underfoot, that is.

The Metropolitan Sewer District (MSD) recently unveiled sweeping changes to the region’s sewage system. By optimizing the existing infrastructure’s ability to handle wet weather, newly-installed smart technologies will reduce environmental risk, slash rates, and prolong its life.

“Our smart sewer system is anticipated to save tens of millions of dollars in capital investments in projects to control sewer overflows,” said MSD Director Gerald Checco in the press release. “This is our best chance of reducing spending and ultimately costs for our ratepayers.”

Prior to this announcement, MSD’s reputation had been marred by a string of scandals. Investigations into their financial practices exposed several improprieties and a once-in-a-century storm flooded homes across the county with backed-up sewage.

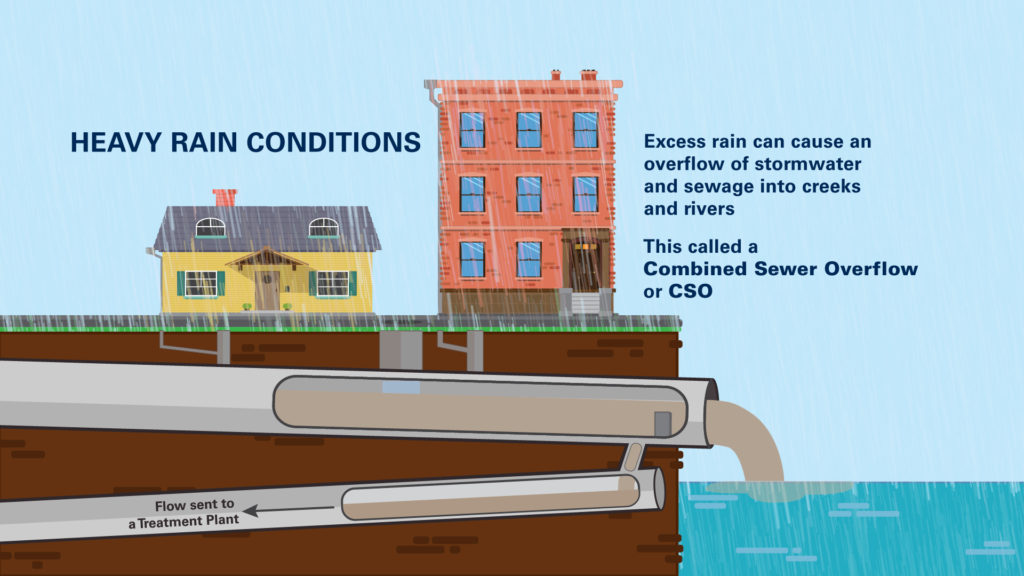

Illustration of a CSO (City of Cincinnati)

Illustration of a CSO (City of Cincinnati)

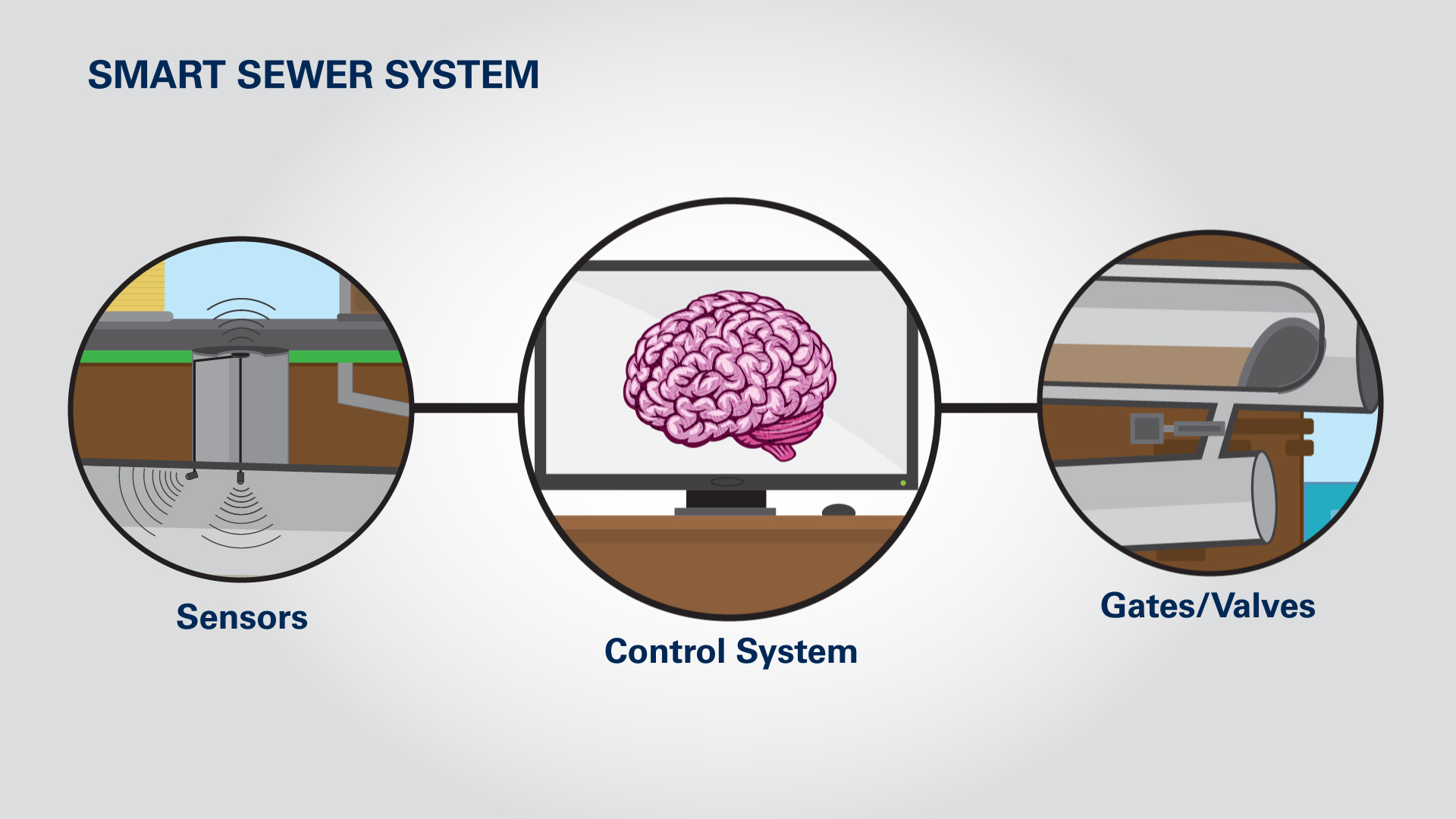

Yet, amid the hoopla, the Mill Creek basin was reaping the benefits of a smart sewer system. A centralized “brain” tracked flow rates throughout the system. New sensors and gates diverted excess storm runoff into larger pipes or other areas that weren’t full. “The ability to have a view of our entire system in real time really helps us to respond quicker to things because it raises that awareness,” said Missy Gatterdam, head of MSD’s watershed operations division, in an interview with UrbanCincy.

Outside this basin, MSD’s pipes empty into nearby streams or rivers, a process called a Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO). CSOs are legal, but they can damage the environment. Sewers combine domestic, commercial, and industrial runoff with storm runoff. On dry days, this is not a problem. Toxic wastes migrate to a treatment facility.

On particularly rainy days, however, the pipes can’t handle all of the waste and water and must dump these undesirables into the ecosystem. (Here is a video MSD made to help explain the process.)

Untreated water isn’t just disgusting; it’s also deadly. An Environmental Protection Agency report to Congress in 2001 says bacteria found in untreated waters can cause gastric disorders, typhoid, and even cholera. Thankfully, MSD’s smart system will reduces the 11.5 billion gallons of runoff and waste overflow that wind up in the region’s waterways every year.

Gatterdam remarked that the original plan was to rollout the technology to the Muddy Creek and the Little Miami River basins this year, but budget cuts by the county have halted any expansion.