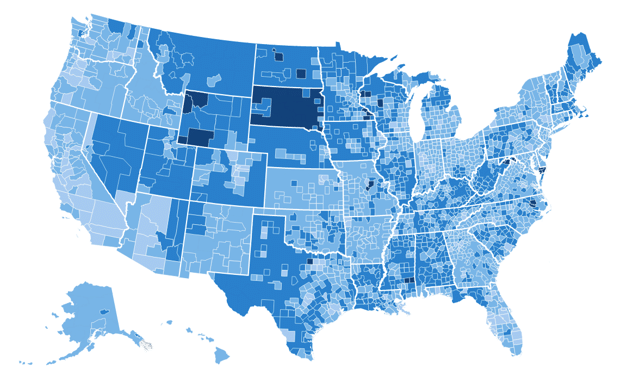

For those at the lowest rungs of America’s economic classes, the affordable housing crisis is bad and getting worse. According to a 2011-2013 study released in 2015 from the Urban Institute, not a single county in the United States has an adequate supply of affordable housing for those in extreme poverty. Families classified as extremely low-income (ELI), or those making less than 30 percent of an area’s median household income, have far less options today than in 2000. On average nationally, only 28 affordable units are available for every 100 ELI renter households. That represents a 25% decrease in the years since 2000, when there were 37 affordable units for every 100 ELI households.

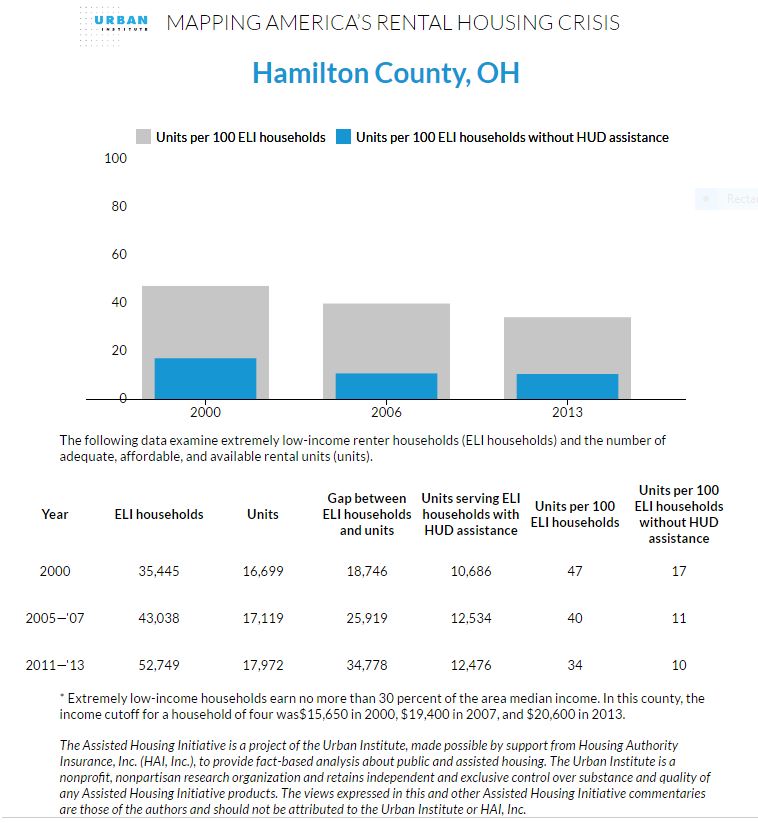

In Hamilton County, there are 52,749 ELI households (making $20,600 or less), with only 17,972 affordable units. This amounts to around 34 affordable and adequate units for every 100 households. In 2000, there were 47 units for every 100 ELI renter households. As usual, most of Cincinnati’s peer cities are facing a similar situation for their region’s poorest residents. In Cuyahoga County (Cleveland), there exist only 31 affordable units out of 100 families today, compared with 44 in 2000. In Allegheny County (Pittsburgh), there are 35 units per 100 families today while there were 44 per 100 in 2000.

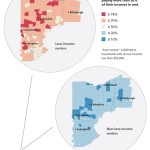

Since 2000, many rural and suburban counties have joined metropolitan counties in their extremely low numbers of available units per needy households. The change is visibly stark on the Infographic for the State of Ohio, As the Urban Institute notes, the most drastic changes have occurred in the Midwest, South, and West in states like Ohio, Kentucky, Alabama, and Nevada, where comparatively abundant ELI housing availability in 2000 has plummeted.

The last 16 years have also seen ELI families increasingly reliant upon federal assistance for housing. The Great Recession, rising prices in many metropolitan areas, stagnant wages, and lack of development mean that while only 57% of families relied on HUD in 2000, more than 80% do now.

Indeed, while the Urban Institute points out that federal assistance for housing has grown (albeit not enough), they also acknowledge that many in the US Congress frequently call for cuts to federal housing assistance provided through the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Without this federal assistance, an already-dire situation for ELI families becomes catastrophic. Accounting for a theoretical total cut in federal housing assistance, there would exist only 5 affordable units for every 100 ELI renter household. That amounts to a mere 609,802 units for 11,341,484 ELI households. In Hamilton County specifically, there would be only 10 units for every 100 households. Cuyahoga and Allegheny Counties fair even worse, with only 5 and 3 units per 100 ELI renter households, respectively.

While the nationwide housing crisis has been much-discussed, including on this site, the true scope of the problem is most visible at the bottom of the economic spectrum. The biggest loss in affordable housing for extremely low income families has occurred mostly in unassisted units, highlighting the need for more affordable developments nationwide. Without increased federal assistance, along with more and smarter development across the nation, many will be driven to homelessness and unsafe & overcrowded housing.