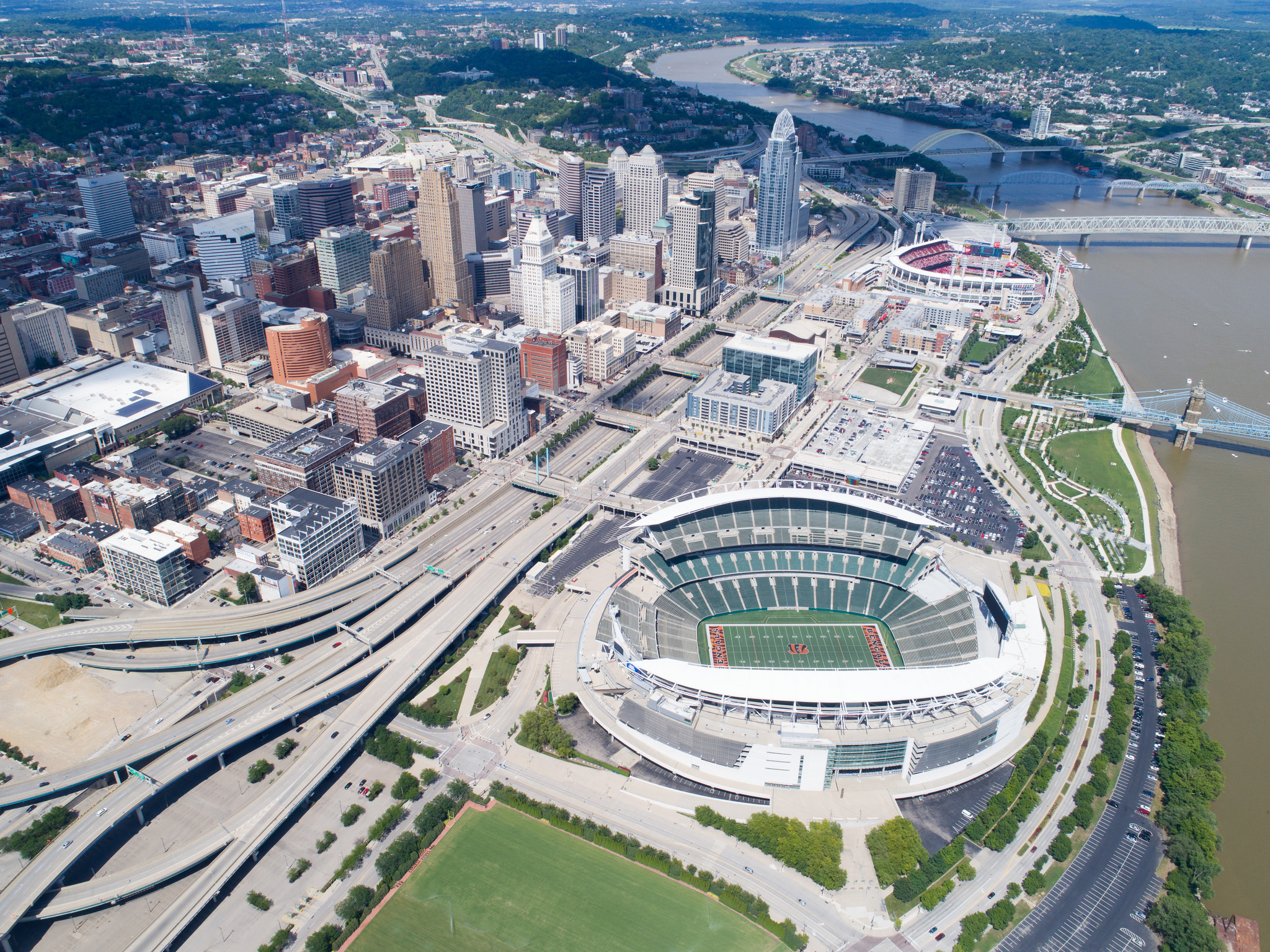

The underlying assumption of the Brent Spence Bridge project is that the level of congestion warrants relief with a new bridge and freeway expansion. The problem of congestion will be solved with new freeway capacity. However, that simple formula does not account for all the costs of the freeway expansion or the benefits not running a freeway through the urban core.

Two important pieces missing from the Brent Spence Bridge project cost/benefit analysis are the value of urban land and induced demand. As noted in a prior article, urban land is valuable. The sustained growth in Over the Rhine is local proof of the national trend that people want to live, work, and play in cities. Proponents of the bridge expansion project assume that the congestion relief is worth the price tag and loss of urban land for the next 50+ years. But what if the congestion relief is ephemeral?

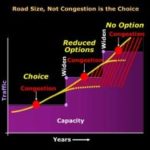

Others in Cincinnati have described induced demand. To reiterate, it is the propensity for freeway lanes to fill to capacity once they are created. New capacity creates new demand. Decreasing the cost of driving with shorter, faster commutes, increases the number of drivers. Road expansions are intended to expand capacity and reduce congestion; however, new freeway capacity quickly fills up and becomes just as congested as before.

There appears to be no upper limit at which enough lanes eliminate capacity. The Katy Freeway in Texas provides the case in point. First constructed in the 1960s, it was six to 8 lanes wide. A $2.8 billion expansion project finished in 2011 that expanded it to one of the widest freeways in North America at 26 lanes: At one segment each direction has 6 lanes of through traffic, 4 feeder lanes, and 3 HOV/toll lanes. Travel times decreased immediately after the expansion, and in 2012 the Katy Freeway was hailed as a success story. However, by 2014, travel times increased 30 percent during the morning commute and 55 percent during the evening commute. $2.8 billion and 18 extra lanes improved traffic for three years, then made it worse than before the project. It achieved congestion relief for less than three years.

The predicted benefits of the Kary Freeway did not last. Cincinnati should learn from that lesson and include the effects of induced demand in the Brent Spence Bridge expansion cost/benefits accounting. The previous design did not adequately analyze induced demand.

Part of the reason that the project did not include induced demand as part of the analysis is that the software used to model traffic volumes is not up to the task. The model, called Static Traffic Assignment (STA), was designed to run on computers from the 1970s. Since you are reading this article on a computer there is no need to explain how much computers have changed in that time. There have been upgrades to the STA software but it retains the same fundamental architecture. STA produces usable predictions for daily traffic volumes but not for peak demand (rush hour). Accurate predictions of peak demand are necessary to understand induced demand.

There are two problems with STA that provide inaccurate peak demand forecasts. First, STA assumes roadway segments are independent, so that a problem in road segment “A” will not impact road segment “B.” In reality, congestion in one road segment does impact adjacent segments. Second, STA allows modeled traffic volumes to exceed capacity. If the model predicts capacity beyond what a given freeway can support, the model will queue vehicles up “outside the model.” In reality, those cars queued “outside the model” are either stuck in traffic or they’ve left the freeway and are taking surface roads to work.

The interstate system is a network that seeks equilibrium. If there is congestion in the network, drivers will avoid it. If there is capacity in the system, drivers will fill it up. The current Brent Spence Bridge project was modeled with STA. STA does not look at the network holistically. It either breaks up the system in segments or moves extra traffic outside the model. The failure to look at the system holistically makes it difficult for STA to predict where induced demand will come from and how intense the demand will be.

A better model now exists to forecast traffic. Called Dynamic Traffic Assignment (DTA), it is a more sophisticated computer model designed to run on contemporary computers. DTA holistically models an interconnected network in equilibrium. If a bottleneck causes a traffic backup, DTA assumes traffic will divert to surface roads rather than move outside the model.

The 2018 CNU Transportation Summit on Highways to Boulevards featured the presentation of a recent paper on DTA. Overall, DTA is a more powerful modeling tool that can better analyze effects on complex systems. There are five vehicular bridges over the Ohio River in Cincinnati, plus the two I-275 bridges. The traffic model must accommodate the regional impact of the bridge expansion on traffic, including the effects of induced demand. This is doubly important if the Brent Spence Bridge expansion is tolled and other bridges are not.

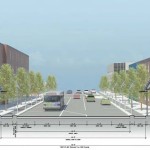

A DTA model of the Brent Spence bridge project will better show the impact of additional vehicles on local streets. Civic leaders in Cincinnati and Covington should have a better accounting of how moving an additional 50,000 vehicles per day through the urban core will affect their street networks, which must be paid for with city tax dollars.

Would it make sense to spend five years building the expansion project if the congestion relief dissipated within five years? Before moving ahead with such a large and expensive project there must be a full accounting of the costs and benefits. Particularly relevant to CNU, the loss of urban land has not adequately been included in the cost of the project. The benefit of congestion relief is diminished by induced demand. There are new tools at hand to better tally up these costs and benefits. A project the size and scale of the Brent Spence bridge expansion project requires a full and transparent accounting of the costs and benefits to move forward.

This is a guest article by Chris Meyer reporting on the 2018 CNU Transportation Summit. CNU and CNU Midwest are content partners with UrbanCincy. Chris is an Architect at Hub + Weber, PLC

If you would like to have your thoughts and opinions published on UrbanCincy, simply contact us at editors@urbancincy.com.