The election held earlier this month marked the 10-year anniversary of MetroMoves, the Hamilton County ballot issue that would have more than doubled public support for the Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority (SORTA). Specifically, a half-cent sales tax would have raised approximately $60 million annually, permitting a dramatic expansion of Metro’s bus service throughout Hamilton County and construction and operation of a 60-mile, $2.7 billion streetcar and light rail network.

MetroMoves was SORTA’s third attempt to fund countywide transit service – sales tax ballot issues also failed in 1979 and 1980.

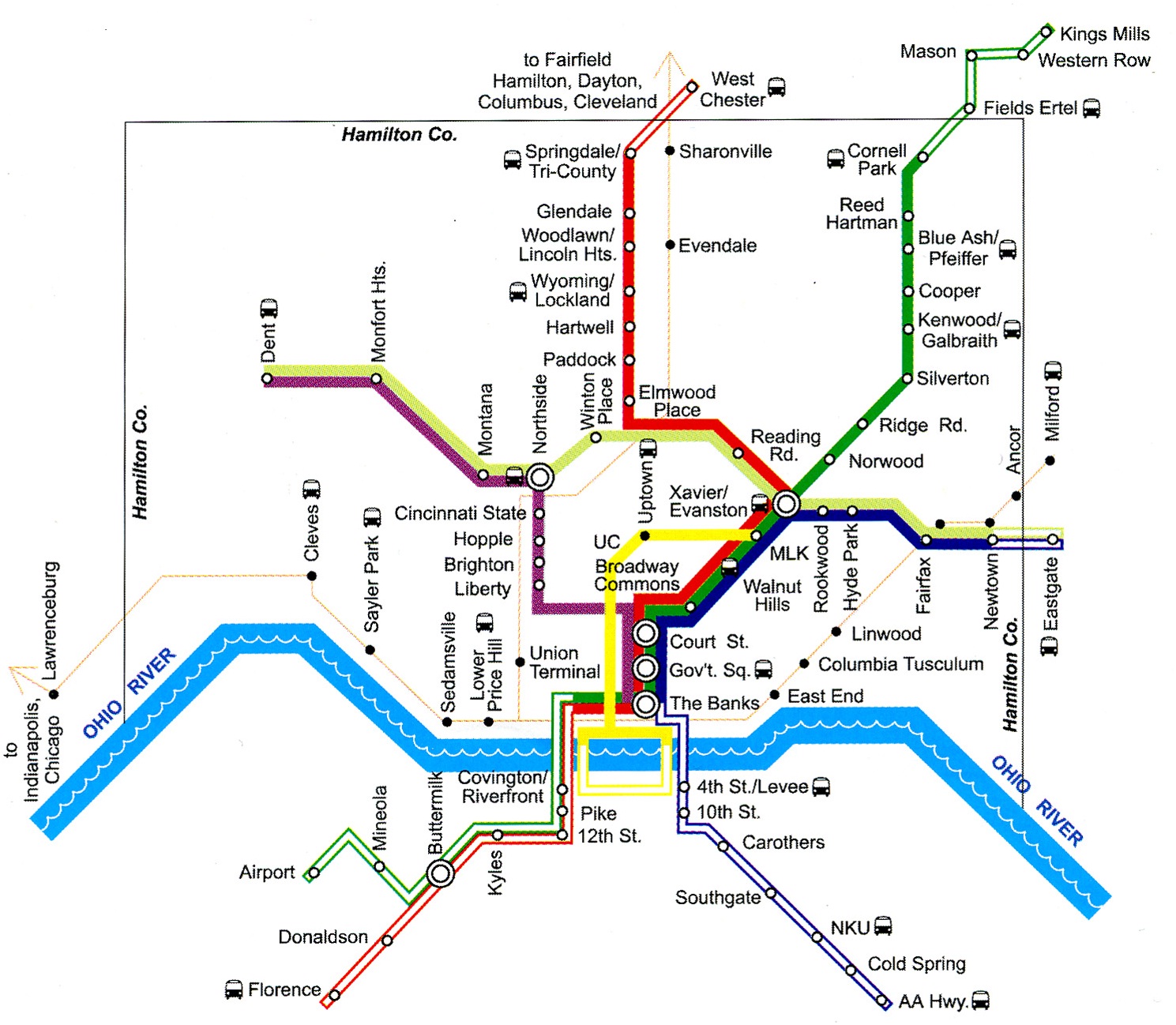

The 2002 MetroMoves plan called for five light rail lines, modern streetcars, and an overhauled regional bus system. Image provided.

Bus System Expansion

According to John Schneider, who chaired the MetroMoves campaign, SORTA planned to expand bus service immediately after collection of the tax began. In 2003 Metro’s schedule would have been reworked with more frequent service on every existing bus line, including more late night and weekend service. By 2004, with the arrival of newly purchased buses, Metro planned to link a dozen new suburban transit hubs with new cross-town bus routes.

The Glenway Crossing Transit Center, which opened in early 2012, is an example of the sort of suburban bus hubs planned as part of MetroMoves. The 38X bus, which began service when the transit center opened, is an example of the sort of new routes that MetroMoves would have funded.

Modern Streetcars & Light Rail Lines

In 2003 design work would have begun on a modern streetcar line and the first of five light rail lines. The streetcar line was planned to follow a route nearly identical to the line currently under construction in Downtown and Over-the-Rhine. The modern streetcar line was planned to have traveled up the Vine Street hill to the University of Cincinnati, then turn east on Martin Luther King Drive, cross I-71, and meet a light rail line on Gilbert Avenue.

Construction would have begun in 2004 and operation would have begun by 2006 or 2007.

The start date for light rail construction was less certain because the MetroMoves tax revenue was to be used as the local contribution for a large Federal Transit Administration (FTA) match. This process became standard practice in cities throughout the country since federal matching began in the early 1970s.

Modern streetcars, similar to those used in Portland, OR, could have been in service as early as 2005 had Hamilton County voters approved MetroMoves in 2002. Photograph provided by John Scheinder.

The first light rail line to be built was the system’s “trunk”, a line connecting Downtown and Xavier University on Gilbert Avenue and Montgomery Road. At Xavier, three suburban light rail lines were planned to converge on a trio of abandoned or lightly used freight railroad right-of-ways.

The first to be built would have been the northeast line through Norwood to Pleasant Ridge and Blue Ash. It was expected that the second line would be one incorporated into a rebuilt I-75; however that highway project has now been pushed back past 2020, meaning the Wasson Road line to Hyde Park likely would have been built soon after the line’s abandonment in 2009.

Renovating the Central Parkway Subway

Lost in the rhetoric employed to defeat MetroMoves was perhaps its most intriguing feature: a plan to renovate and at last put into use the two-mile subway beneath Central Parkway. This tunnel was built between 1920 and 1922 as part of the Rapid Transit Loop, a 16-mile transit line that would have connected Downtown with Brighton, Northside, St. Bernard, Norwood, Oakley, and O’Bryonville. Construction of the Rapid Transit Loop ceased soon after the Charterite ouster of the Boss Cox Machine and never resumed.

Three subway stations at Race Street, Liberty Street, and Brighton were to have been renovated and put into use as part of the 2002 MetroMoves plan. North of the subway’s portals, the line would have traveled on the surface to Northside, then entered I-74’s median near Mt. Airy Forest. Park & Ride stations were planned in the I-74 median at North Bend Road and Harrison Avenue/Rybolt Road in Green Township.

A fifth light rail line, requiring construction of four miles of new track, was planned to connect Northside and the Xavier University junction. Trains on this fifth line would travel from the far West Side to Hyde Park on the I-74 and Wasson Road corridors.

MetroMoves failure at the polls

MetroMoves was placed on the November 2002 ballot by SORTA in anticipation of a new federal transportation bill in 2003. What became known as SAFETEA-LU, a $286.4 billion measure, was not passed until 2005. Although SORTA’s board had the authority to place a transit tax on Hamilton County’s ballot in the years before the federal transportation bill was passed, MetroMove’s 2002 defeat was so lopsided (161,000 to 96,000 votes) that the regional transit authority choose not do so.

When speaking with those affiliated with the 2002 MetroMoves campaign, the failure of the ballot issue is usually attributed to four key factors:

- Anti-tax mood caused by the 1996 stadium sales tax and ensuing cost overruns

- 2001 Race Riot

- The MetroMoves campaign was thrown together quickly during summer 2002. SORTA’s board did not vote to place the issue on the ballot until August 20.

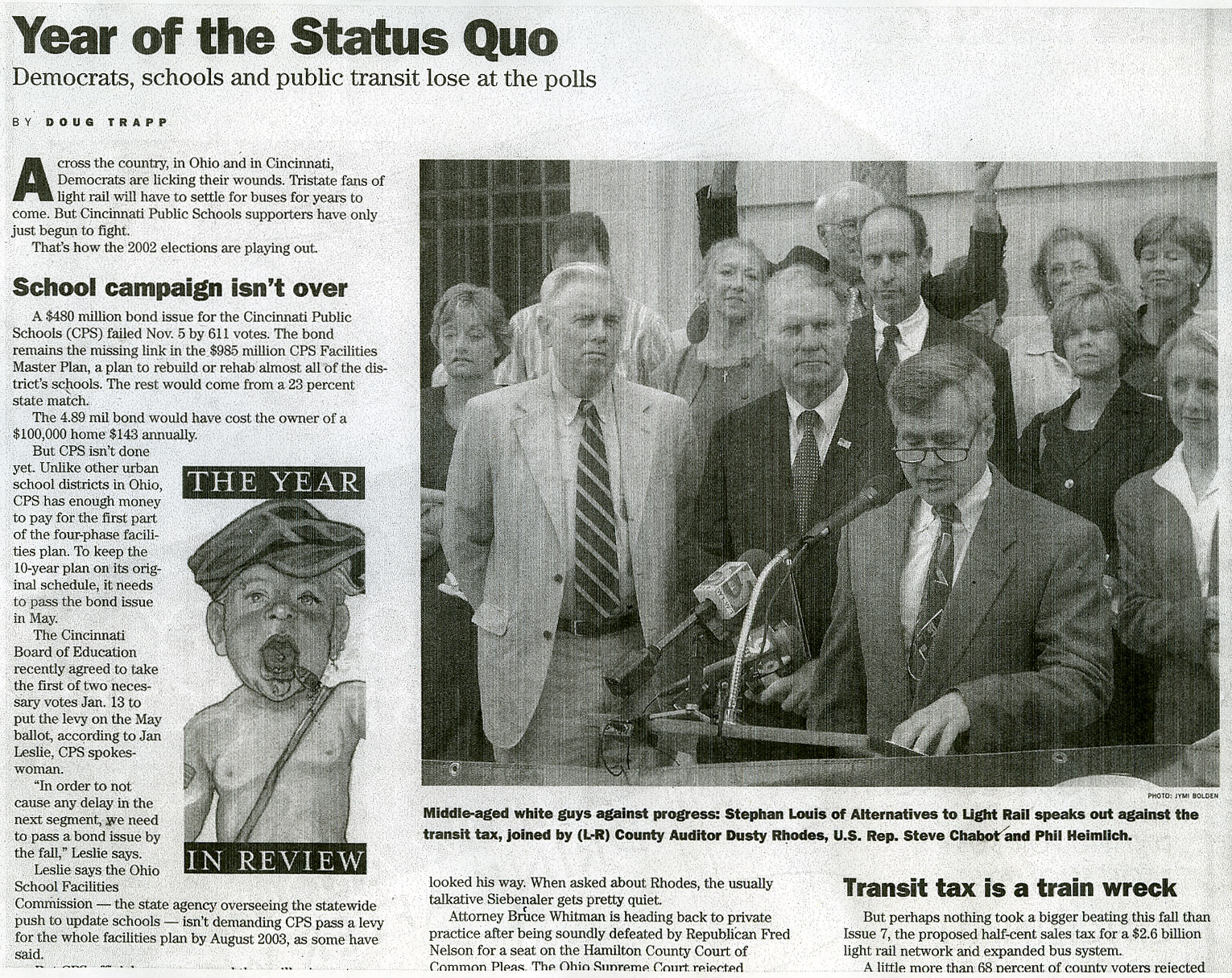

- A dirty opposition campaign comprised of Hamilton County Auditor Dusty Rhodes (D), Commissioner John Dowlin (R), Commissioner Phil Heimlich (R), and Congressman Steve Chabot (R).

The opposition campaign was led by Stephan Louis, who in late 2002 was reprimanded for false statements made during the campaign by the Ohio Elections Commission. Nevertheless, as a reward for his work in opposing MetroMoves, he was soon after appointed to SORTA’s board along with fellow public transit opponent Tom Luken in 2003.

Opponents to the 2002 MetroMoves campaign were accused and found guilty of using unethical campaign tactics. Newspaper image taken from a 2002 issue of CityBeat.

In 2006, Louis came under fire for having written racist and anti-public transportation emails and was forced off the board soon after. He reappeared to campaign in support of COAST’s anti-streetcar Issue 9 in 2009 and Issue 48 in 2011.

Another MetroMoves?

In 1972 when Cincinnati voters approved the .3% earnings tax that enabled creation of a public bus company, it was expected that city funding would be temporary and Hamilton County would eventually fund the region’s public transportation. Instead, nearly 40 years later, Cincinnati’s bus company is still funded only by the city and therefore provides only limited service outside city limits.

Ten years after the defeat of MetroMoves, despite a tripling of gasoline prices and the viability of transit systems proven by an increasing number of mid-sized American cities, it seems unlikely that a similar effort stands a chance of passage in Hamilton County in the immediate future. Many of the same public figures who opposed MetroMoves ten years ago have acted repeatedly in the past five to obstruct Cincinnati’s current streetcar project.

Furthermore, since the election of President Barack Obama (D) in 2008, the Tea Party has fomented an irrational suspicion of local government, and local anti-tax groups have authored intentionally misleading ballot issues. Meanwhile our local media, especially talk radio, continues to harass public transportation at every opportunity.

The way forward for the Cincinnati area has, since 2007, been the City of Cincinnati by itself. Despite the efforts of politicians, anti-tax groups, and utility companies to stop Cincinnati’s streetcar project, it broke ground in early 2012 and track installation will begin next year. Along with ongoing demographic shifts within Hamilton County, the success of Cincinnati’s initial streetcar might persuade the county’s electorate to approve county funding of public transportation for the first time.