Cincinnati is set to join the ranks of American cities with bike sharing with the launch of Cincy B-Cycle next summer. The program is being organized by Cincy Bike Share, Inc. and is expected to begin operations in June.

Cincinnati is set to join the ranks of American cities with bike sharing with the launch of Cincy B-Cycle next summer. The program is being organized by Cincy Bike Share, Inc. and is expected to begin operations in June.

Jason Barron, who previously worked in the office of former mayor Mark Mallory, was hired as the non-profit organization’s executive director in early December.

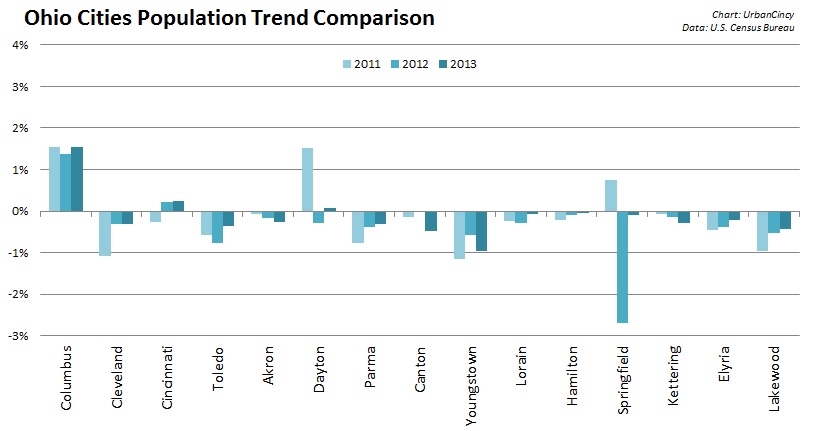

Over the last several years bicycle sharing programs have begun operating in several dozen cities across North America, and many more are planned. In July, CoGo Bike Share started operating in downtown Columbus and surrounding neighborhoods – marking the first bike share system to open in Ohio.

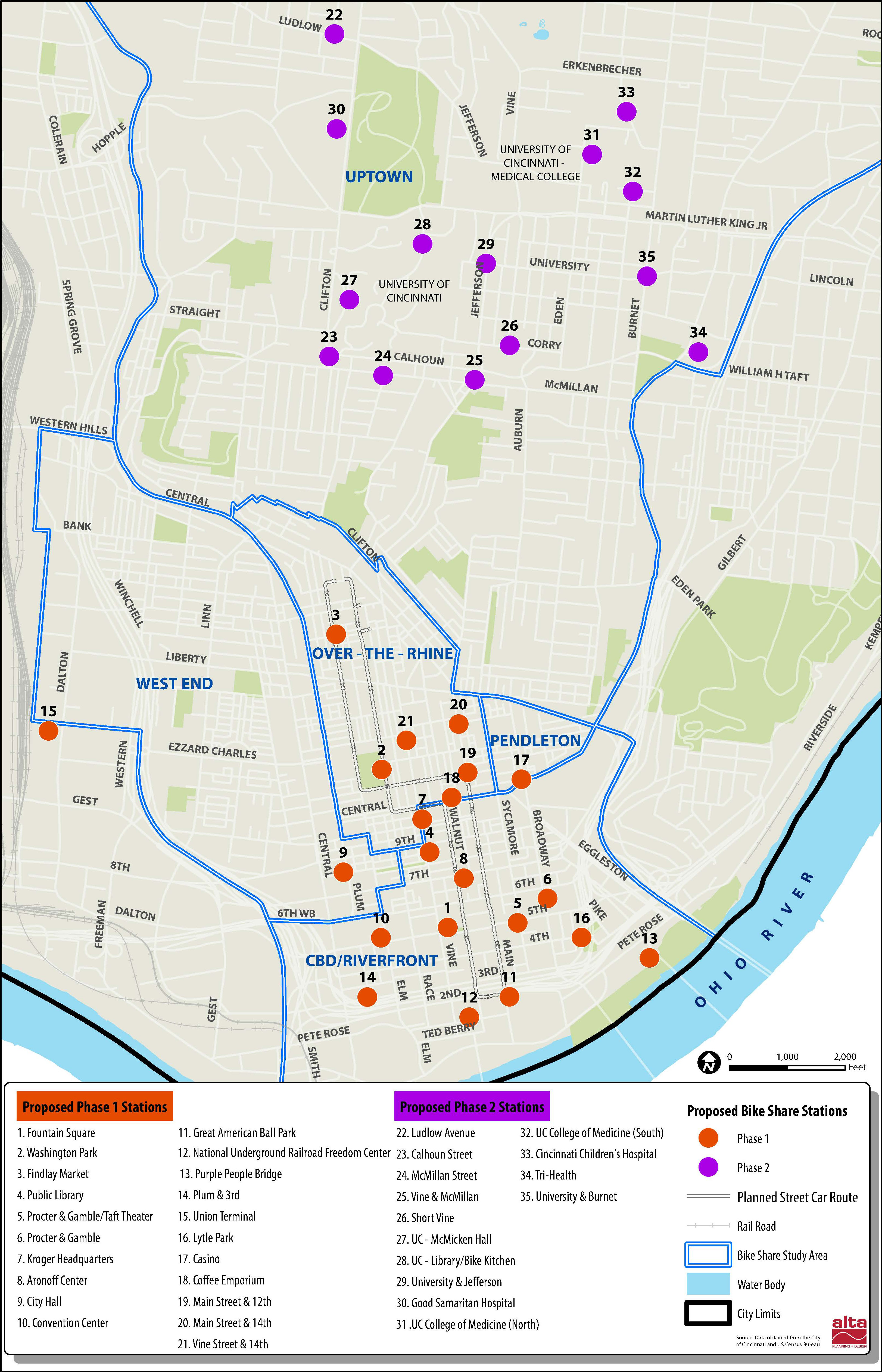

The planning for Cincinnati’s bike share system has been underway since 2011, when the Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber’s Leadership Cincinnati program started looking at getting a program running here. Then, in 2012, a feasibility study was commissioned by Cincinnati’s Department of Transportation & Engineering (DOTE).

It was not until the summer of 2013, however, that Cincy Bike Share, Inc. was established, and quietly selected B-Cycle to manage the installation and operations of the program.

B-Cycle operates bike share programs in over 25 cities in the United States, including Kansas City and Denver, and has started expanding overseas.

While traditional bike rentals are oriented to leisure rides, with the bike being rented for a few hours and returned to the same location, bike sharing, on the other hand, is geared for more utilitarian use.

According to Barron, usage of shared bikes is intended for one-way rentals over shorter time periods. Bikes are picked up and dropped off at unattended racks, where they are locked with a sophisticated system that is designed to allow users to quickly make trips that are just beyond walking range – often times about a half-mile to two miles in length.

The way the systems usually work is that users can either purchase a monthly or yearly membership that entitles them to a certain number of rides per month. Non-members, meanwhile, are typically able to purchase passes by the hour or day and are able to pay by cash or credit card at the informational kiosk present at each station.

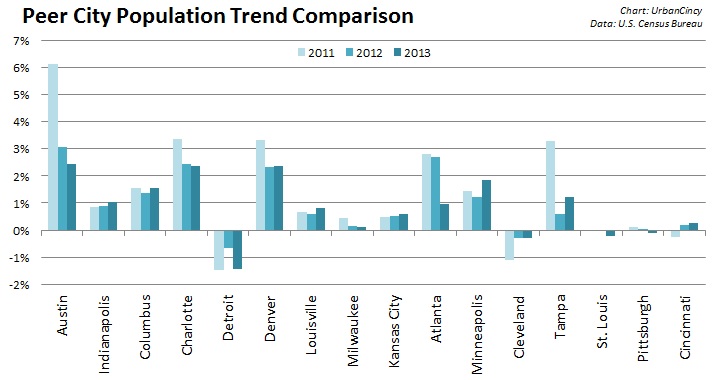

Proponents view bike share programs as attractive components in the development of vibrant cities. With the continued revitalization of Cincinnati’s center city, Barron feels that bike share will fit well into the mix.

“With all systems of transportation, the more the merrier” Barron explained. He went on to say that he hopes that bike sharing, cars, buses and the streetcar “will work together to give people some great mobility options.”

One of the remaining tasks for Barron and the newly established Cincy Bike Share organization will be securing the necessary funding to build the approximately $1.2 million first phase of stations and the $400,000 to operate it annually. Barron believes that it can be accomplished through a number of ways including through a large number of small sponsors, as was done in Denver, or signing one large sponsor like New York City’s CitiBike system.

In addition to added exposure, bike share advocates point to research that shows improved public perceptions for companies sponsoring bike share systems. In New York, it was found that Citicorp’s sponsorship of CitiBike led to greatly increased favorability of the bank shortly after that bike share program launched.

“It’s a tremendous opportunity for a corporation to tap into the young professional market,” Barron told UrbanCincy.

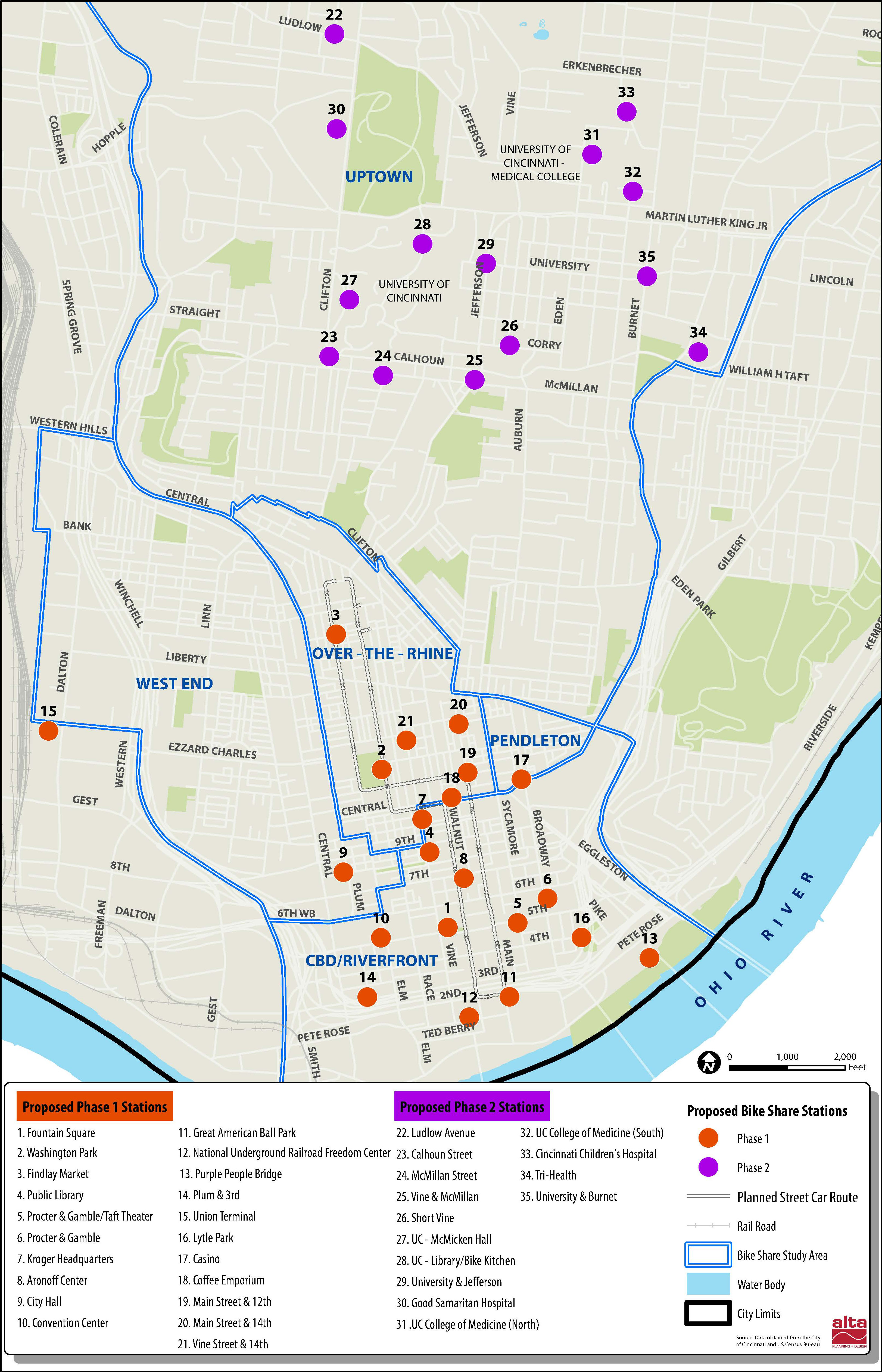

Cincy Bike Share is planning to start operations with about 200 bikes based at about 20 stations in downtown and Over-the-Rhine in the first phase, and would include a total of 35 stations with 350 bikes once phase two is built. Cincinnati’s initial system is modest in size when compared to other initial bike share system roll outs in the United States.

New York City CitiBike: 6,000 Bikes at 330 Stations

Chicago Divvy Bike: 750 Bikes at 75 Stations

Boston Hubway: 600 Bikes at 61 Stations

Atlanta CycleHop: 500 Bikes at 50 Stations

Miami DecoBike: 500 Bikes at 50 Stations

Washington D.C. Capital Bikeshare: 400 Bikes at 49 Stations

Denver B-Cycle: 450 Bikes at 45 Stations

Columbus CoGo: 300 Bikes at 30 Stations

Cincinnati B-Cycle: 200 Bikes at 20 Stations

Salt Lake City GREENbike: 100 Bikes at 10 Stations

Kansas City B-Cycle: 90 Bikes at 12 Stations

Cincinnati’s bikes are expected to be available for use 24 hours a day, and Barron says they will also most likely be available for use year-round. Cincy Bike Share will be responsible for setting the rate structure. While not final yet, it is estimated that annual memberships will cost $75 to $85 and daily passes will run around $6 to $8.

The 2012 feasibility study also looked at future phases opening in Uptown and Northern Kentucky. While it may be complicated to work through operating a bi-state bike share system, Barron says that Cincy Bike Share has already discussed the program with communities in Kentucky and says that they have expressed interest in joining.

While there is no state line or a river separating the systems initial service area downtown from the Uptown neighborhoods, steep hills at grades ranging from 7% to 9% do. These hills have long created a barrier for bicyclists uptown and downtown from reaching the other area with ease.

Barron views the hills as an obvious challenge, but part of Cincinnati’s character and what make Cincinnati great. When the Uptown phase gets under way, he says that it will be operated as one integrated system with the first phase, but that it is not known yet how many users will ride between the two parts of the city.

Over the past few years, the DOTE’s Bike Program has greatly increased the city’s cycling infrastructure, and it is believed that continued improvements will help make using this new system, and the increasing number of cyclists, safer on the road.

Cincinnati’s new bike share system also appears to have majority support on council and with Mayor John Cranley (D), who has publicly stated that he is in favor of the program. “We plan on working with the City as a full partner,” Barron noted. “We think everything’s in place.”

If everything goes according to plan, the initial system could be operational as early as this summer.

Salt Lake City GREENbike photographs by Randy Simes for UrbanCincy.