Downtown Cincinnati is home to five Fortune 500 companies, three professional sports teams, local businesses, and according to the 2010 U.S. Census, about 5,300 residents. But the area is also home to more than 35,000 off-street parking spaces.

These spaces once held historic buildings but have been demolished to provide automobile parking over the years. As downtown continues its resurgance, it would be prudent for city leaders to review its outdated parking policies.

In the middle part of the 20th century, many cities, including Cincinnati, developed zoning codes with regulations dictating how many parking spaces are required for different uses. The regulations often accounted for “peak demand,” which is the amount of parking planners believed would be needed at times where demand for parking would be the greatest. For example, accounting for Black Friday-type events where parking lots are only maxed out once or twice a year.

Hundreds of brand new parking spaces in downtown Cincinnati’s Central Riverfront Garage sit unused. Photograph by Randy A. Simes for UrbanCincy.

In his article, The Trouble with Minimum Parking Requirements, UCLA professor Dr. Donald Shoup writes, “Minimum parking requirements are intended to satisfy the expected peak demand for parking at every land use–at home, work, school, banks, restaurants, shopping centers, movie theaters, and hundreds of other land uses from airports to zoos. Because the peak parking demands at different land uses occur at different times of the day or week, and may last for only a short time, several off-street parking spaces must be available for every motor vehicle.”

The demolition of buildings that are mostly historic is also a concern as downtowns struggle to build parking infrastructure that is required by code. Those demolitions, oddly enough, systematically demolish the very things that distinguished them from the suburbs and made the area an appealing destination.

In Nashville, TN, city leaders first removed parking requirements for older buildings, and then moved to remove parking requirements for all buildings in their city center.

“Requiring parking for historic structures that have never had parking is incentivizing their demolition. This puts the property owner in a really difficult position; he must either find parking for the building, demolish it or let it languish in perpetuity.” Nashville city planner, Joni Priest, told UrbanCincy. “If a property owner wants to rehab an historic building – a building that marks the character of a neighborhood and contributes to the fabric of the city – all incentives, including the elimination of parking requirements, should be considered.”

Parking mandates also increase the upfront cost to developers looking to invest in urban neighborhoods. Additional land, often still occupied by historic buildings, must be purchased in order to provide the required parking spaces at approximately $10,000 to $25,000 per space, depending on land and architectural fees. Those costs are then passed on to the consumer, making urban living or starting a small business more expensive.

Contemporary parking mandates can make it nearly impossible for developers and city planners to build neighborhoods like Over-the-Rhine any more. Photograph by Randy A. Simes for UrbanCincy.

Parking requirements also have impacts that are not quite as obvious. Increased parking capacity, in theory, increases the amount of cars in the given area and puts an added burden on downtown streets. Even though the traditional grid pattern is ideal for dispersal of traffic in urban settings, downtowns are ideally designed to accommodate people. Cities that add parking, or widen streets for automobiles, do so at the expense of pedestrians.

Even as city leaders work to implement a plan to increase downtown vibrancy through additional residential space and increased foot traffic, concern for parking punctures the debate on how to further support the urban core.

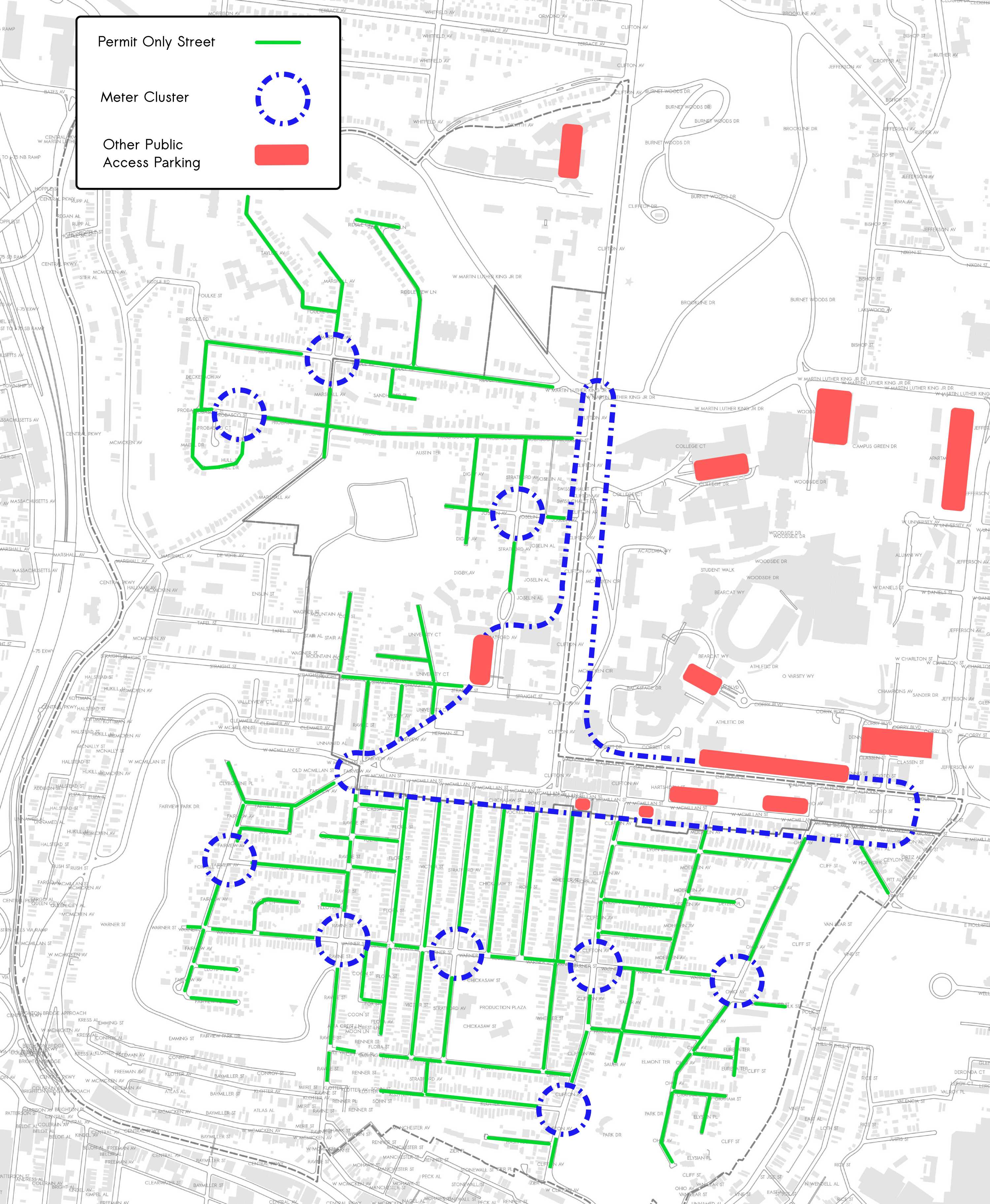

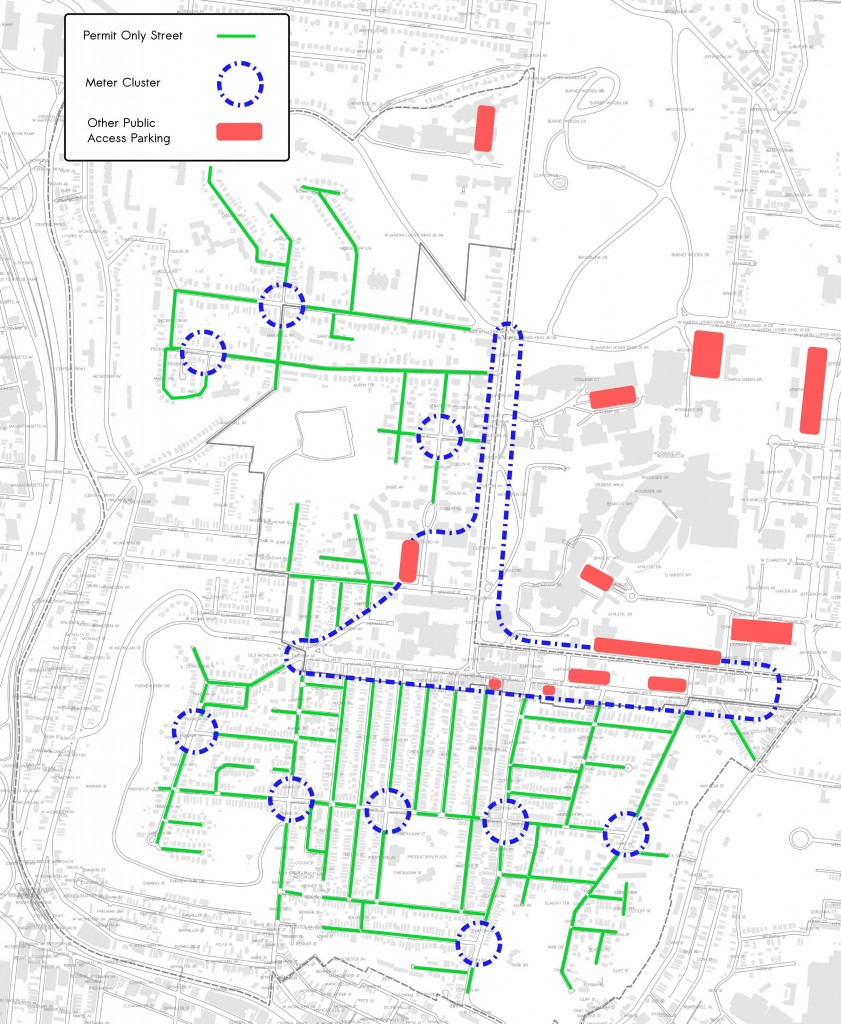

The urban parking analysis UrbanCincy conducted in 2010 identified many of these problems, but no significant action has been taken to-date aside from the reduction of parking needed to be provided along the Cincinnati Streetcar route.

City leaders need to seriously reexamine their policies on the matter, and they could get started by discussing the following three potential solutions:

- Eliminate Parking Mandates – As city leaders were able to do in Nashville, we believe Cincinnati leaders could do the same and remove the minimum parking requirements forced upon investors in the city’s urban core.

- Cap and Trade System – First proposed by UrbanCincy in 2010, this innovative system has been implemented in several European cities such as Amsterdam, Hamburg and Zurich. Regulations are designed to limit the total number of parking spaces in an urban area, and provide incentive bonuses while limiting parking. Parking spaces are created on a case-by-case basis and often involve repurposing on-street parking spaces for other uses such as community gardens or parks.

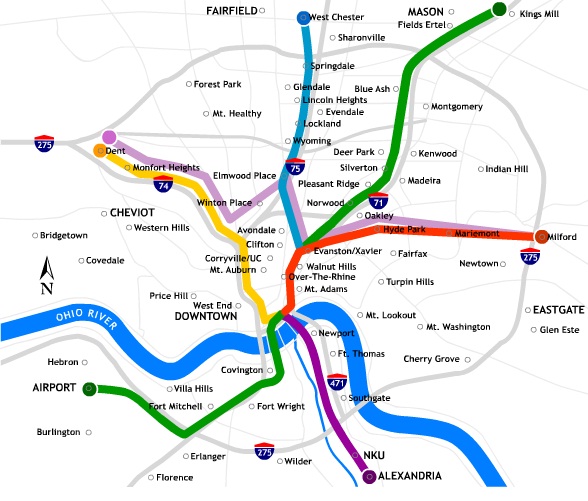

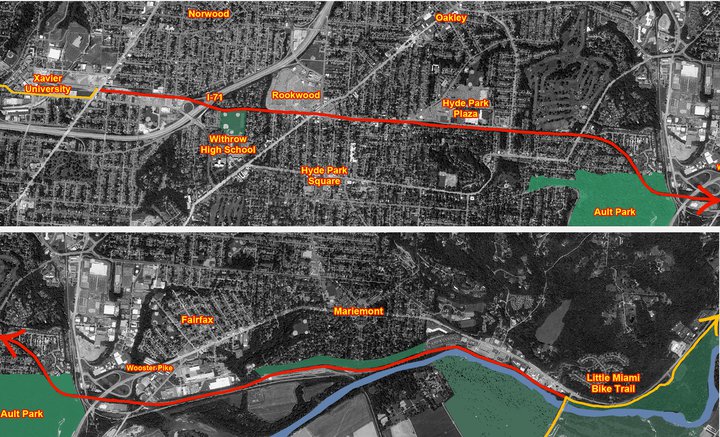

- Set Parking Maximums – Instead of dictating a minimum, parking requirements are capped by use or developed density. This strategy has been employed in New York City where development of parking has been limited in an attempt to reduce the impact of automobile traffic on the already densely developed island of Manhattan. Parking maximums seem to work with the availability of alternatives to driving. Therefore; if Cincinnati were to pursue this route, it should be in conjunction with the implementation of more efficient alternatives from Metro including expanding streetcar routes, light rail and bus rapid transit alternatives.

While the need for reform appears evident, a contextualized solution should be pursued by Cincinnati city officials that specifically tailors the policy to localized needs. What may be most important is offering flexibility to small businesses and investors who are looking to invest in Cincinnati’s urban core.

“Removing the parking requirements from downtown zoning allows flexibility for site-specific and program-specific solutions,” said Priest. “Flexibility is key in urban environments. As downtown becomes more comfortable for pedestrians, cyclists and transit users, new development will have the flexibility to build less parking.”