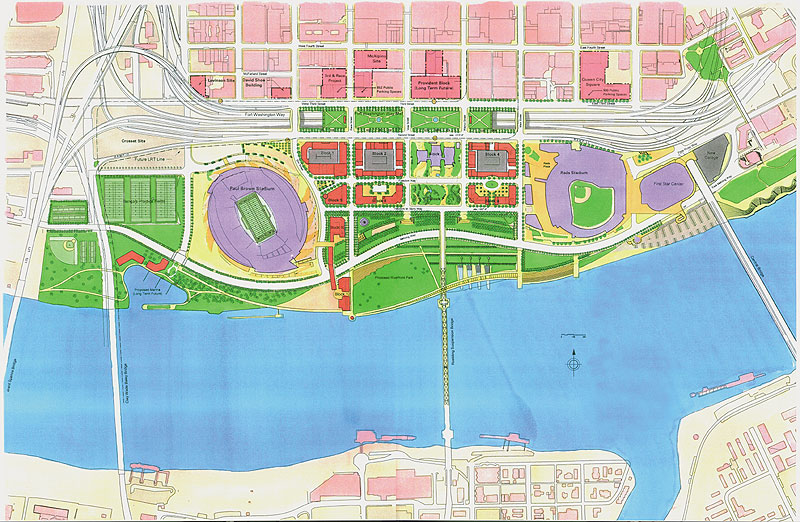

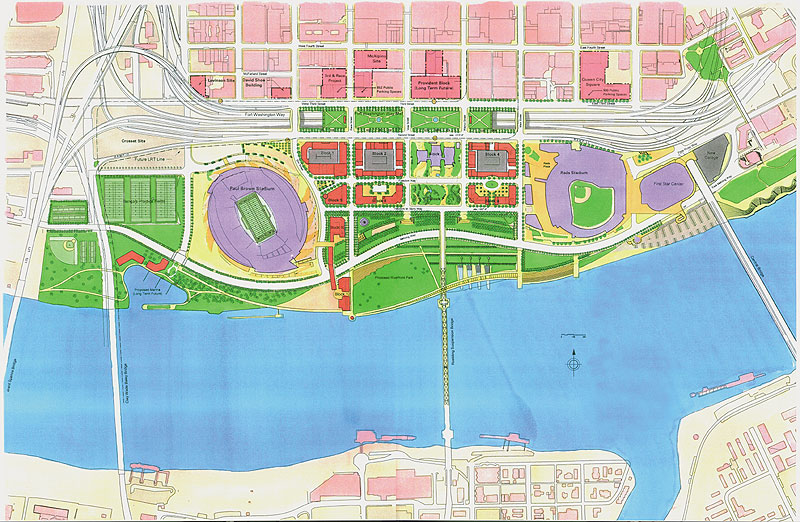

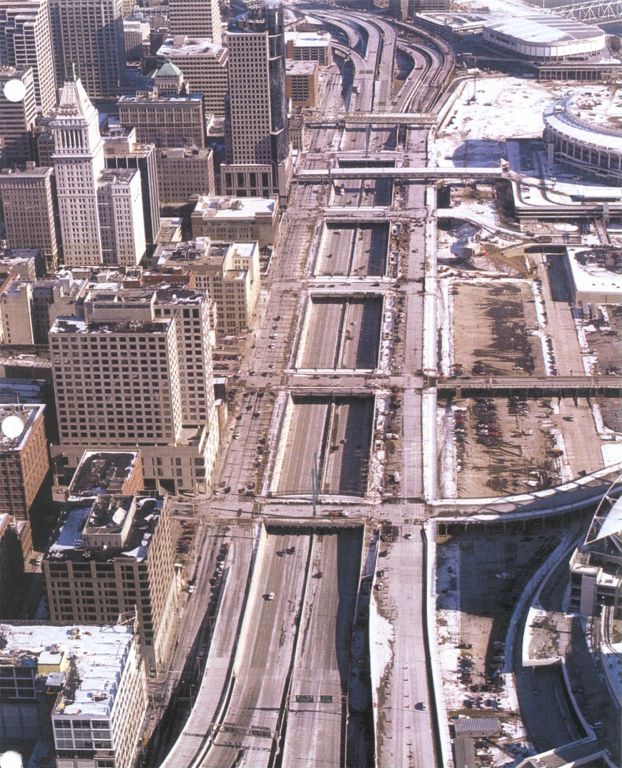

Each Wednesday in July, UrbanCincy is highlighting Fort Washington Way (FWW), the I-71/US-50 trench bisecting the Cincinnati riverfront from its downtown. Part one of the series discussed what the area looked like prior to reconstruction a decade ago, and how that reconstruction made way for the development along Cincinnati’s central riverfront. Last week’s article discussed some of the unseen assets included in the project that continue to benefit Cincinnatians in a variety of ways today. This week’s piece will highlight even more of the unique features that the 1.25 mile-long highway boasts.

In addition to the combined sewer overflow fix along Cincinnati’s central riverfront through added containment capacity, engineers also increased the capacity for municipal water under Third Street. This led to an opportunity for the City of Cincinnati to share its high-quality water supply with communities in Northern Kentucky through a new tunnel built underneath the Ohio River. Those in Kentucky benefit by receiving clean water, and the City of Cincinnati benefits from an increased revenue stream.

On the southern side of the FWW trench is a wall that supports Second Street and conceals the Riverfront Transit Center, but it also serves as the primary flood protection for downtown Cincinnati. Cincinnati choice to build its flood protection into its everyday infrastructure maximizes utility while also conserving urban space. Since this wall was engineered to lift Second Street above the floodplain, it effectively extended the street grid south while also maintaining safety.

The benefits discussed so far were not accomplished in isolation. In fact, the reconstruction project was helped paid for by entities in the state of Kentucky including the Transit Authority of Northern Kentucky (TANK) who saw better connections with Cincinnati as an economic gain. The project fixed the entanglement of on- and off-ramps to the bridges over the Ohio River, and has led to a better transfer of people and goods across the state line.

The fact that the Cincinnati area calls so many large and lucrative companies home demonstrates that the city once had the ability to draw major economic players to the region. The fact that they have stayed demonstrates that the area has done well to keep up with changing business, technological, and infrastructure demands. One such example of keeping up with changing times can be found buried under Third Street, behind the northern wall of Fort Washington Way, where engineers included the capacity for a bundle of fiber optic cables, approximately three feet in diameter, spanning the length of the roadway.

This dark fiber has the capability to be activated and connected with a larger fiber optic network when needed, ensuring that downtown Cincinnati has the ability to stay at the cutting edge of technology. Possible uses include connecting large-scale data centers to the Internet backbone, or providing high-speed fiber-to-the-home Internet access for Cincinnatians, such as Cincinnati Bell’s FiOptics or Google’s Fiber for Communities.

Next Wednesday’s article will conclude the series, and look to the future of the area. What can be done with the space over the FWW trench in terms of the capping? How will future development be impacted? And, ultimately, will the reconstruction of Fort Washington Way reestablish the strong ties that once existed between Cincinnati and its riverfront?