A new report released by the Center for Transit-Oriented Development finds that transit investments like the Cincinnati Streetcar are winning economic winners. The report studied the three most recently opened light rail lines in the United States and discovered that urban portions of the lines were most successful at spurring economic activity and ridership.

Contrary to popular belief that rail transit is only successful in liberal bastions like Portland, San Francisco, New York, Chicago, Washington D.C., Philadelphia or Seattle, the report looked at three modest cities in terms of political affections: Charlotte, Denver and Minneapolis.

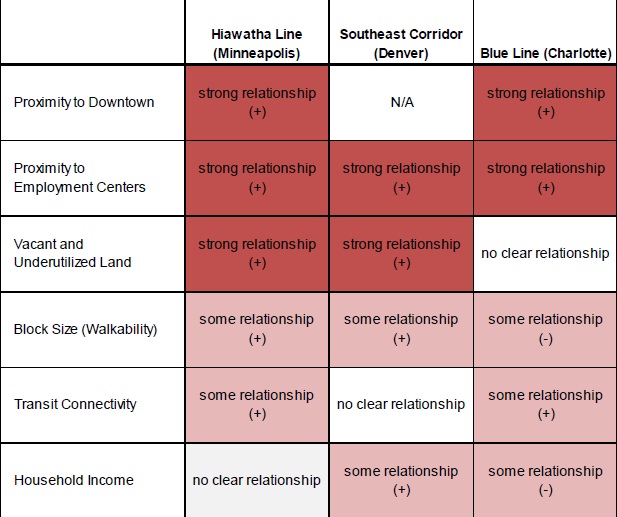

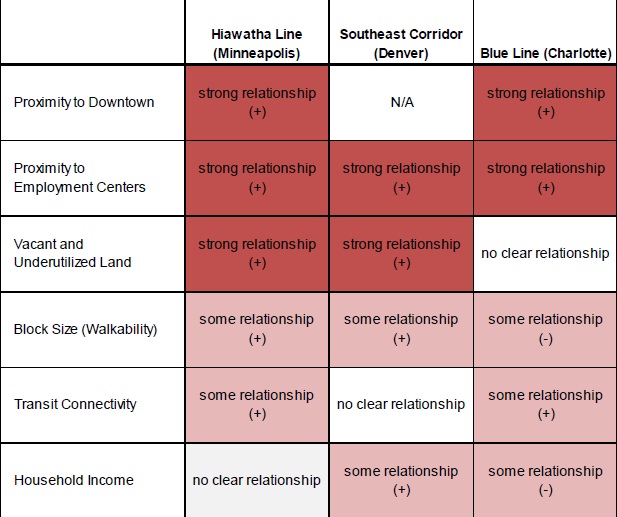

Rails to Real Estate: Development Patterns along Three New Transit Lines also identified Charlotte’s Blue Line as the most successful despite being the having the least number of years studied of the three and being the smallest of the three transit lines. The economic patterns were consistent though, with each transit line experiencing anywhere from six to ten million square feet of new development since they opened. The report attributes the success is to five main considerations:

- Proximity to downtowns and other major employment centers

- The location and extent of vacant or “underutilized” property that might offer opportunities for development or redevelopment

- Block patterns that influence “walkability”

- Transit connectivity

- Household incomes

“We need to make transit investments that unlock the potential for TOD, but we need to make them in the right places,” said the director of the Center for Transit-Oriented Development, Sam Zimbabwe.

Cincinnati’s modern streetcar system has recently been challenged by Ohio Governor John Kasich (R) in regards to its ability to generate economic investments and create jobs. This challenge goes against economic studies performed by HDR Economics and confirmed by the University of Cincinnati’s award-winning economist George Vredeveld. When applying the key findings of the Center for Transit-Oriented Development’s recent report Cincinnati’s streetcar system looks to be an even bigger winner than expected by the OKI Regional Council of Governments (OKI) and Ohio Transportation Review Advisory Council (TRAC) which have both enthusiastically supported the project.

The Cincinnati Streetcar meets all five of the reports key considerations for economic success along transit lines. The system runs through downtown Cincinnati and connects the regions two largest employment centers, and serves areas that include vacant and underutilized properties that offer opportunities for development or redevelopment. The Cincinnati Streetcar also connects with the region’s focal point for bus transit, serves a block pattern that is extremely walkable, and includes a diverse range of household incomes.

And while the report shows Charlotte as the big winner, its findings show that the Cincinnati Streetcar could be even more successful than the Blue Line’s approximately 9.8 million square feet worth of real estate investment between 2005 and 2009. The main reason is, of course, location.

Cincinnati’s streetcar line will serve an area better equipped and positioned for transit-oriented development (TOD) when compared to Charlotte’s Blue Line which saw economic investments drop off precipitously after leaving that city’s downtown (Uptown) and adjacent residential neighborhood (South End). When compared to Charlotte, Cincinnati’s downtown and adjacent residential areas (Over-the-Rhine, Clifton Heights, Mt. Auburn, Corryville, University Heights) served by the streetcar line represent significantly greater land area prime for TOD.

Major economic investments are already occurring on and around the Cincinnati Streetcar line in anticipation of its opening in 2013. In Clifton Heights the $70 million U Square at The Loop mixed-use development derives its name from its proximity to the streetcar’s connection to Uptown. In Over-the-Rhine Rookwood Pottery, Christian Moerlein, the $400 million Horseshoe Casino Cincinnati and dozens of small businesses have expressed their hopes for the eventual opening of the modern streetcar system. And in downtown developers of The Banks and other major developments have begun using the Cincinnati Streetcar as a marketing tool.

In addition to the existing positives for Cincinnati’s streetcar system when it comes to TOD, the planned streetcar system also has local planning efforts supporting it. In 2010 Cincinnati City Council passed a measure that will reduce or eliminate parking requirements at residential developments within two blocks of a streetcar stop. The streetcar system will also be managed with the Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority (SORTA) which currently operates Metro bus service and plans to coordinate the two systems.

The report noted that while transit improvements were a factor in the real estate investments, that coordination with longer-term efforts to revitalize center cities was greatly important.

“This study marks an important step in understanding the impact of transit investments in three regions, and the implications for other communities looking to transit investments as a source of long-term economic prosperity and competitiveness,” Zimbabwe stated. “Investments in neighborhood infrastructure and amenities are critical for unlocking the potential for TOD.”

When the study examined the differences between the lines in Charlotte, Denver and Minneapolis it showed that the urban portions were most successful at attracting economic investment. Charlotte’s Blue Line (9.6 miles) saw approximately 1,021,000 square feet of development per mile, while Denver’s Southeast Corridor (19.1 miles) and Minneapolis’ Hiawatha Line (12.3 miles) saw 408,000 and 545,000 square feet of development per mile respectively.

The results from this study are clear for transit-oriented development. An urban setting with opportunities for development, close proximity to job centers and transit connectivity are critical for economic success. Suburban areas show diminishing returns in the form of economic activity and real estate investment along transit line. The Cincinnati Streetcar represents all of the key considerations and more, and is exactly why the project has received TRAC’s highest score for two consecutive years out of every transportation project in Ohio.