New data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, which covers Ohio, western Pennsylvania, the West Virginia panhandle, and the eastern half of Kentucky, provides a glimpse into the recovery and transition of the region’s economy.

According to the newly released data, spanning from 2001 to 2012, this Federal Reserve region has weathered an incredibly tumultuous 11 years.

“Historically, much of the region has specialized in manufacturing, a sector that has been particularly hard hit over the past few decades,” noted Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland research analyst Matthew Klesta in his data brief. “Since the end of the Great Recession in 2009, however, the decline in manufacturing employment has slowed. In some places, employment has even grown.”

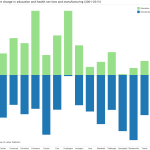

Since the first year of recorded information in this data set, all 17 Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA) in the region, with the exception of Wheeling, WV, saw losses in manufacturing employment – the region’s historical economic stalwart. MSAs like Dayton and Steubenville posted losses of almost 50%. Cincinnati, meanwhile, saw its manufacturing sector decline by nearly 25% – a mark that is low by regional standards.

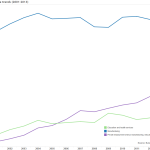

International trends in trade in the early 2000s, like China’s entry into the WTO and the increase of offshoring from developed to developing nations, combined with the Great Recession, dealt a critical blow to the area’s manufacturing sector. Excluding education and health services, every other industry in the region saw significant jumps in the annual percentage of jobs being lost during the Great Recession.

For example, between 2001 and 2007 the average loss per annum for the manufacturing sector was a little less than 3%; but from 2008-2009 it jumped to nearly 7%. Since the Great Recession, however, many MSAs in the area have posted modest gains in manufacturing employment, while still falling well below baseline levels in 2001.

While the manufacturing sector has declined throughout this Federal Reserve region, health and education sectors have grown. Despite a nationwide average of 1.2 health and education service jobs gained per 1 manufacturing job lost, only four MSAs in the region (Cincinnati, Columbus, Huntington, Pittsburgh) can boast an overall replacement of lost manufacturing jobs with health and education employment.

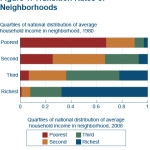

The replacement of manufacturing jobs with health and education employment does not bode well for the region’s workers. According to the data, the health and education sectors pay, on average ($44,000 in 2012), significantly less than manufacturing ($55,000 in 2012).

But while this changing economic landscape has meant a smaller presence for manufacturing in the region, this Federal Reserve Bank region continues to be highly specialized in that economic sector. Perhaps as a result, population loss continues to plague many MSAs within the region.

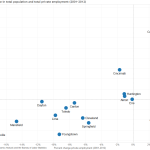

From 2001-2011, while the national population grew by 10% the regional population posted an average gain of only 1.6%. In fact, only five (Cincinnati, Huntington, Akron, Columbus, Lexington) of the 17 MSAs in the region saw their population rise over that time period. Of those five metropolitan areas, only two (Lexington and Columbus) posted gains in both population and private-sector employment.

Pittsburgh and Wheeling, meanwhile, managed to post positive gains in private-sector employment while still shedding population. The remaining 10 MSAs all posted losses in private-sector employment and population.